Why we should get used to being worried about asteroids crashing into Earth

The most scare about an asteroid strike has passed – but advances in technology mean we can now see more and more of them out there in space, writes Andrew Griffin

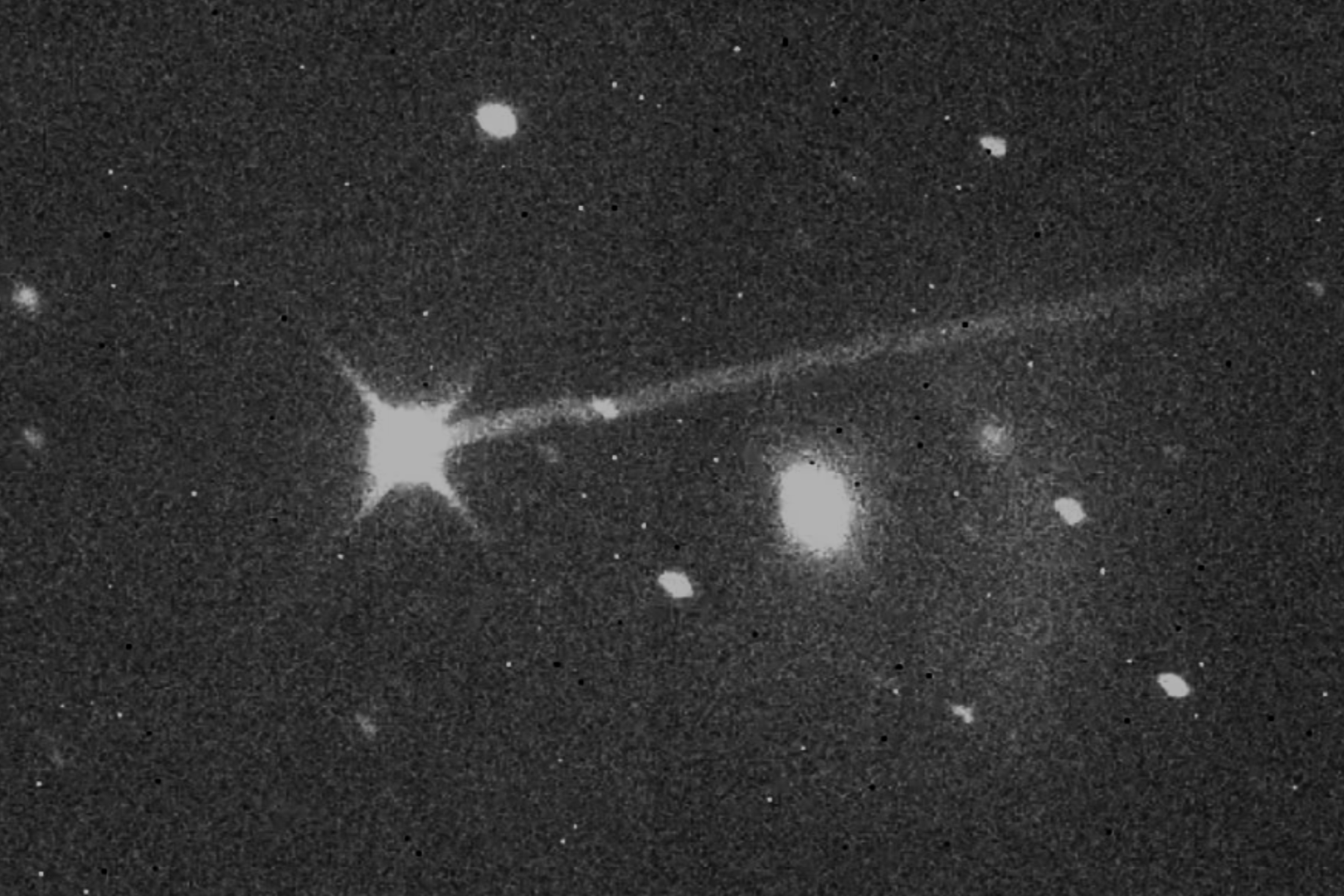

The world wasn’t in need of another reason to panic, but asteroid 2024 YR4 gave them one anyway. It was first spotted at the end of last year, and in the days that followed it went from minor curiosity to major concern as astronomers came to worry that it might hit Earth when it flies towards us in 2032. More observations meant that its chances of hitting Earth ticked up, and so did the press coverage, and by February it was being regularly described as a city killer or a potential apocalypse.

Astronomers said there was little reason to worry. The chance of a collision only ever reached 3.1 per cent – a record for an asteroid of its size, but still tiny. Even at its worst, its rating on the Palermo scale never got over zero, which means that Earth is actually more at risk of being hit by another, unknown object.

Richard P Binzel knows better than most how worried we should be. In fact, he invented the scale for it. The Torino scale was modelled on the Richter scale and Binzel’s hope was that it would be used in much the same way: a quick way of understanding exactly how much devastation a natural disaster would pose. When it comes to both asteroids and earthquakes, that devastation tends to be less than might be feared.

The scale gives specific information about who exactly should be worried about an asteroid. Level one is marked as “normal”, and advises there is no cause even for “public attention”; it then progresses up through “meriting attention by astronomers” (2-4); at five, it suggests that “governmental contingency planning may be warranted”. It’s only really when an asteroid gets to level eight – which no asteroid has ever been anywhere near – that the scale enters the “red zone” and panic might be encouraged.

Speaking from his office in Colorado, surrounded by trinkets of a career spent tracking asteroids, Binzel certainly does not look panicked. “These objects are there – they have always been there,” he tells The Independent. An object like YR4 probably passes as close to us as the Moon is every month, he notes; the meteor showers that intermittently dazzle us down on Earth are themselves caused by the small specks of space dust that we collide with as we fly through the solar system.

“What’s changing is our ability to see them out there – and right now our capability to discover small things far away exceeds our ability to track them for a long time,” he says. That means we can discover lots of asteroids, but don’t necessarily know where they’re coming from or going, which makes it difficult to know exactly whether they might hit us or not.

Scientists also tend to like to work that out in public, which means that people can see very well just how uncertain they are. For decades, astronomers and policy experts have wondered whether that’s the best approach, since most potentially hazardous asteroids will turn out to pose no threat at all, and so there is the danger of either undue panic or boy-who-cried-wolf apathy. But Binzel says there is little option anyway: the asteroids are up there in the sky for anyone to spot, and so it wouldn’t be possible to keep them secret from the world.

He acknowledges that this means that astronomers might come in for criticism. The chances of a collision with 2024 YR4 are now rapidly falling, and at the time of publication are close to zero; as the panic fades, there is a chance that the public will instead become annoyed that they were ever worried. But “it’s a price we pay for being open – we just kind of sigh and say that’s just how it’s going to be. It’s the price for honesty”, he says.

Astronomers might very soon have much more to talk about. Later this year, the Vera C Rubin Observatory in Chile will be switched on, and it will start taking a broad and detailed view of the sky. In 2027, after a run of budget problems and delays, Nasa hopes to launch the NEO Surveyor, a space telescope specifically made to find potentially hazardous asteroids.

That means that we will see more asteroids; many of them might pose at least some threat to us, though of course they would be there whether we saw them or not. With that new era of astronomy could come a new era for worry, as there are more objects to panic about bringing life on Earth to an end.

But it could also allow for a newly informed sense of just how much danger we are in. Californians are used to checking the Richter scale to know whether they need to worry about a given earthquake, and that knowledge will often actually turn out to be calming; those who live in the Gulf of Mexico are used to checking whether they are at risk from a given hurricane and responding accordingly.

Binzel likens it to having your house expected and finding faulty wiring: the danger was always there, now you just know about it. In the case of asteroids, the job of responding to that danger might be huge: Nasa has tested sending spacecraft to smash into asteroids and redirect them, for instance. The world would have to come together to undertake something bigger and with higher stakes than perhaps anything ever before. But we would be able to respond, at least.

“Whatever the danger is, there’s either an object out there with our name on it or there isn’t,” says Binzel. “But we’re worse off not knowing what’s out there, because we could be taken by surprise; we’re increasing our security by finding these objects.” Until then, there’s little we can do but wait.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments