Books of the month: What to read this March from a twisty thriller to Julian Barnes on changing your mind

Martin Chilton shares his March reading highlights

Anne Sebba’s The Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz: A Story of Survival (Weidenfeld & Nicolson) is a tale of endurance, revolving around the inspirational force of music and the sheer power of small acts of kindness. The book, a well-researched study that includes first-hand accounts about surviving Nazi death camps, is also a testimony to the strength of female solidarity in the most wretched circumstances. As one of the musicians puts it: “Who can understand these people? One moment they want Schumann’s “Träumerei”, the next moment they are putting people in the fire.”

One of the more unusual books out this month is Willow Winsham’s The Story of Witches: Folklore, History and Superstition (Batsford). Witches are believed to have helped stop Napoleon from invading England; in his book, Winsham notes that thousands of witches across the United States “took part in a ritual against president Donald Trump” in 2017. Maybe spells just ain’t what they were.

The best reissues of March include Faber’s paperback editions of three classic Samuel Beckett novels: Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnamable. In the new introduction to Molloy, Colm Tóibín reminds readers of Beckett’s ability to mix the tender and the savage in his writing, as well as his penchant for providing “less than wholesome” humour.

The autobiography, novel and non-fiction books of the month are reviewed in full below.

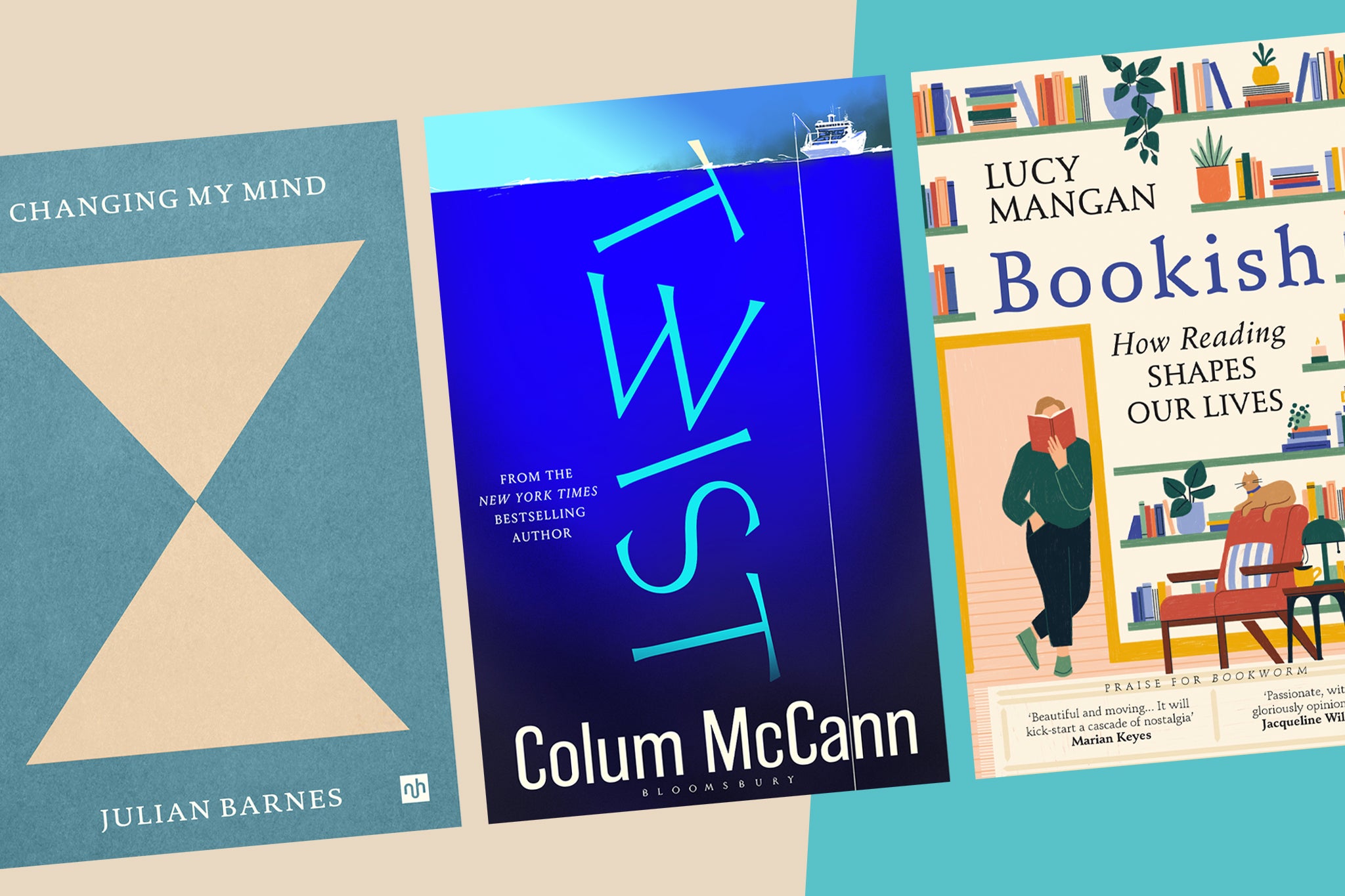

Autobiography of the month: Bookish: How Reading Shapes Our Lives by Lucy Mangan

★★★★☆

-copy.jpeg)

Lucy Mangan’s Bookish: How Reading Shapes Our Lives is the follow-up to the journalist’s 2018 release Bookworm: A Childhood Memoir and picks up as a sort of ongoing autobiography from her teenage years. The choice presented to adolescent girls in the 1980s, she writes, was to be placed in the “bimbo box” (aiming to be attractive to boys by being “pretty, booby, acquiescent”) or the geeky box and endure “the awkward teenage years for the bookish” as a result.

Elsewhere, The Guardian TV critic offers interesting thoughts on how GCSE curricula can damage children’s relationship with literature; she provides a solid defence of “guilty-pleasure reading”, including of Shirley Conran’s 1982 novel Lace, a scandalous “bonkbuster” of its time. I’m pretty much in agreement with Mangan about the value of escapist fiction, although we have different tastes. For example, she admits to being one of many adults who loved the Harry Potter books, confessing that when she worked at the Bromley Waterstones she waited “as eagerly and impatiently as any of our child customers” for the next instalment in JK Rowling’s series.

Bookish also deals with reading when you are pregnant (can she be alone among expectant mothers who were given a copy of What to Expect When You’re Expecting and then hurled it across the room?) and ends with lockdown – “when books saved me”.

Most touching are the moments in which she recalls her late father (who died in January 2023) and her memories of how he used to buy her treasured books. Bookish is certainly for the bookish – an affectionate, warm guide to the healing power of reading.

‘Bookish: How Reading Shapes Our Lives’ by Lucy Mangan is published by Square Peg on 13 March, £18.99

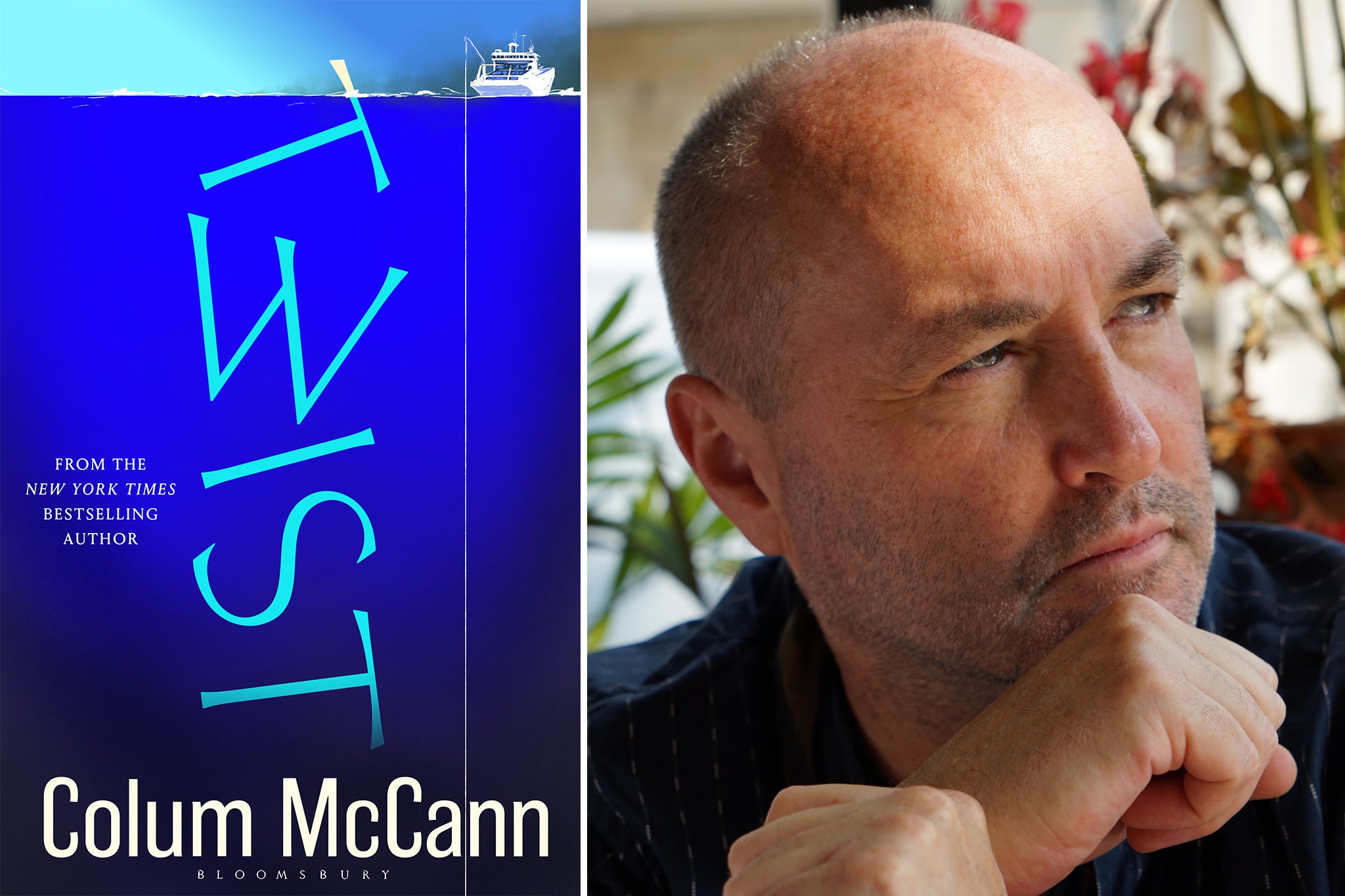

Novel of the month: Twist by Colum McCann

★★★★★

Colum McCann’s Apeirogon was one of my books of the year for 2020, so I approached Twist with high expectations. They were not misplaced. His new novel, about an Irish journalist and playwright called Anthony Fennell and his assignment to write about the underwater cables that carry the world’s information, is simply stunning.

Fennell travels to Cape Town to board the Georges Lecointe, a cable repair vessel captained by chief of mission John Conway, a mysterious and reckless freediver who repairs shattered fibre-optic tubes at unfathomable depths. When the mission falters and Conway disappears, Fennell tries to find him in what becomes part thriller and part exploration of narrative and truth. (There are deliberate echoes of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.)

The other main character is Conway’s estranged wife Zanele, an actor and ocean lover who offers some stark views on what is happening to the waters that Conway inhabits. She tells Fennell that four billion tons of industrial waste is being dumped in the sea every year. “If this was happening in a f***ing sci-fi movie, we’d get it, but we don’t,” she says. “If we had any sense, we would all die of shame.”

There are vivid descriptions of the sea (“everything gets filtered out except the blue, it’s like being in a Miles Davis song,” says Conway) and of the drinking that has wrought such damage on Fennell’s complicated private life.

Twist is a truly thought-provoking novel about truth, the universal propensity to “misdirect” when it comes to our own character, and the shoddiness of the web age and what Fennell calls “the obscene certainty of our days”. It is hard not to conclude that whatever benefits technology brings, internet connection comes at the price of human disconnection.

The 21st-century human seems a very broken thing in Twist. And McCann’s novel, penned by a brilliant storyteller at the height of his powers, has a disconcerting ability to help you simultaneously find and lose your bearings.

‘Twist’ by Colum McCann is published by Bloomsbury on 6 March, £18.99

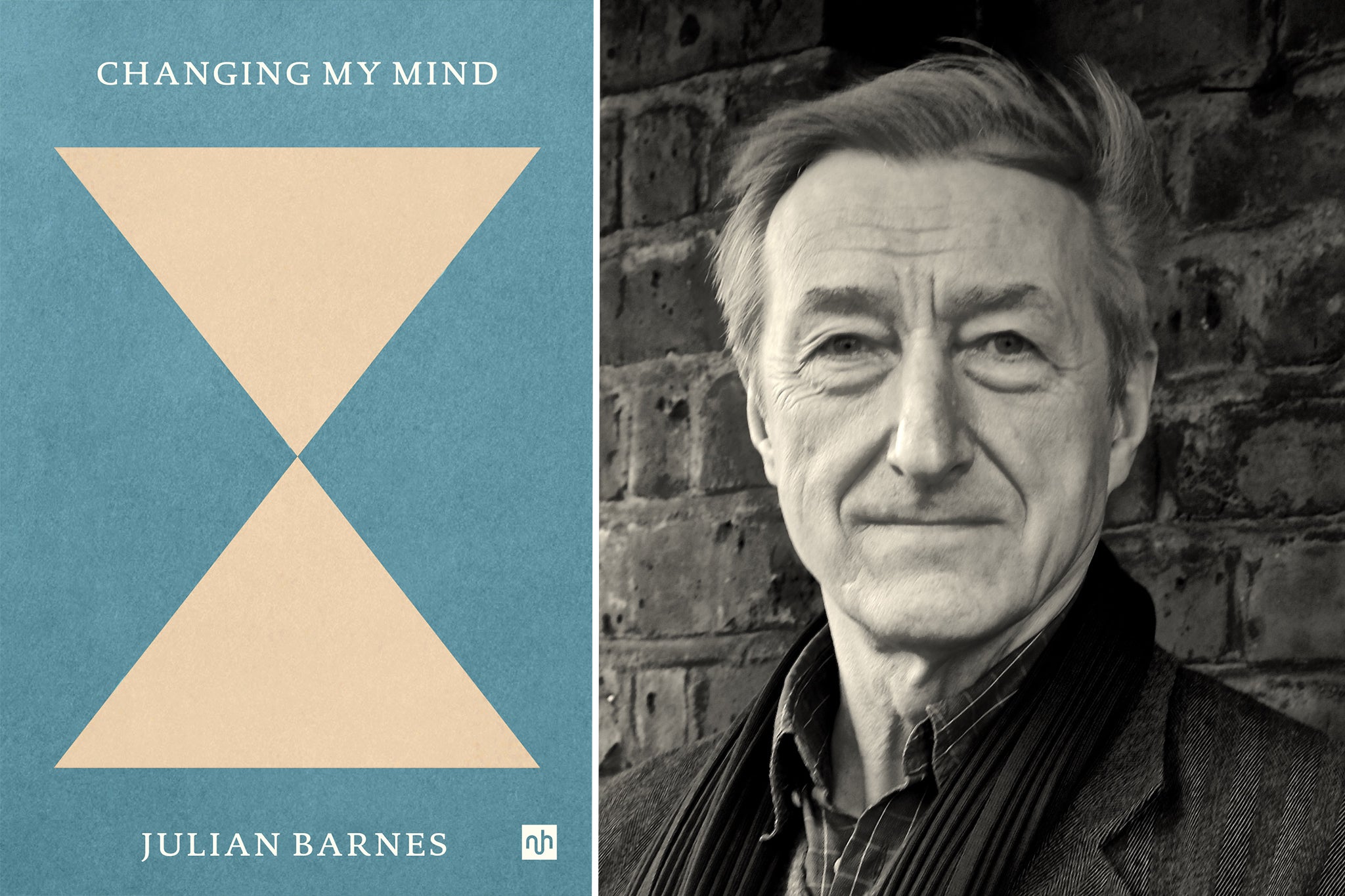

Non-fiction book of the month: Changing My Mind by Julian Barnes

★★★★☆

Fellow oldies past their prime will surely offer a nod of recognition at Julian Barnes’s ruminations on “how memory degrades”. It arrives in the Memory section of Changing My Mind (a collection of essays partly broadcast on radio a decade ago), in which Barnes explains how he has altered his opinion over the years and now believes that “memory is a feeble guide to the past”. Late in life he now believes, like his philosopher brother as it happens, that a single person’s memory is no better than an act of the imagination when it is uncorroborated and unsubstantiated by other evidence.

Changing your mind is a running theme across the book’s four other sections – Words, Politics, Books and Age and Time – which are all provocative and entertaining. The section on politics is perhaps the most revealing. Barnes, who was born in 1946 and who remains one of Britain’s finest modern novelists, writes that the only time he voted Conservative was in the early 1970s, when it was a choice between Edward Heath and Harold Wilson. He also offers an amusing account of what would happen in “Barnes’s Benign Republic”. Among his pledges are a 50-year ban on any Old Etonian from becoming prime minister and turning at least one royal palace into a museum of the slave trade.

Barnes offers a sane, sardonic guide to the world and demonstrates why it is beneficial to have flexibility of thought. He changed his mind about the merits of author EM Forster, for example, after reading a delightful description of a breakfast Forster was served on a boat train to London in the 1930s: “Porridge or prunes, sir?”. The book is perfect for a reflective hour or so of reading. Although it is slight (57 pages in a small octodecimo format), less is definitely more with Changing My Mind.

‘Changing My Mind’ by Julian Barnes is published by Notting Hill Editions on 18 March, £8.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments